TL;DR

Conducted full-time summer research at the University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute (UMTRI) Human Factors group with Dr. Brian T.W. Lin on naturalistic human car following behavior modeling and interpretation. Explored dataset with statistical and data-driven learning methods to learn about the dataset. Created a GPU-based simlulator and parameter-optimizer for five car following models. Qualitatively show human's "lift and coast" behavior during congestions that is not modeled by classical parametric car-following models. Research paper "Evaluating Parametric Car-Following Models in Naturalistic Congestions: Insights in Driver Behavior and Model Limitation" accepted to the Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting 2025.

While this research experience has gone in a completely different direction than I expected when I completed my application, this journey offered me great personal growth and professional development opportunities. My literature review capabilities was vaslty enhanced as I crunched through the over 90 papers and book chapters I reviewed before starting our manuscript. As someone with only one year (actually just 3 months of active) driving experience and no professional insights in this field whatsoever, I quickly grasped the core of car-following behavior research, and analyzed existing data to reveal previously un-noticed and un-modeled human behavior. The struggle to find a good research question, struggle of communicating research goals and action items with my mentor, dealing with the leave of my mentor and a transition in research direction, and the pressing timeline towards a breakthrough all forged my character and resilience as a researcher that never say never.

- Download the Project Poster.

- Download the TRBAM 25 Manuscript.

- Get the open source Source Code.

From Autonomous Vehicle to Driving Behavior

When I applied for the U-M Summer Undergraduate Research in Engineering program, my mentor, Dr. Lin's autonomous driving vehicle project deeply attracted my attention. It was a great combination of practical work that would reflect and reinforce my professional skills, as well as a great opportunity to work with the state of the art algorithms and be exposed to opportunities to bridget sim-reality gap for an intelligent system.

Upon our first meeting after my acceptance to the project, however, Dr. Lin unfortunately informed me that this project was not funded, so we needed to switch to a different project, which involves more data processing and analytics of car following. This marks the unexpected start of my first summer research experience. Despite not being as familiar with theoretical work and data-driven modeling, I was sure that this is invaluable opportunity for my research skills and critical thinking, no matter how difficult the path may be.

Back and Forth

At the start of the meeting, my mentor set the overall goal of the project to be "finding patterns in car following behaviors", a rather vague goal I must admit. This was the opening of over a month of data exploratory work where I examine the patterns in data, compute some statistical properties, cluster the data points individually (more on this later). Over the first month of the project, I was already running a few neural network configurations on these datasets and learning about time-series prediction tasks in the ML space, since that was what I was interested in. I even managed to get the (at the time) all new Komologorov Arnold Networks (KAN) running on our dataset, hoping to uncover previously unseen relations between environment observations and driver reactions. My mentor, while not familiar with deep learning research, was encouraging my work every time we meet and was pleased with the progress I've made. What I did not realize at the time was that my lack of definitive research question and my mentor's reservation of criticism were leading us on the wrong track.

It was not until five weeks into my research journey did a big disturbance turned the course of this experience: my mentor decided to leave UMTRI for personal reasons. Although he will be mentoring my project in an unofficial way, he brough in Dr. Arpan Kusari as my official supervisor at UMTRI, to support me administratively. Still, for Dr. Kusari's insights into machine learning methods and transportation research, I insisted that we invite him for our weekly, sometimes twice a week status meetings. It turned out to be a great choice. In our first meeting, Dr. Kusari was keen to point out that while I have been focusing on data-driven models, which have great performance but poor explainability, Dr. Lin was thinking more about parametric model studies. After this meeting, the research question became much clearer: determining differences among parametric car-following models, and potential difference to naturalistic human driving behavior.

The Human Factor

How Models Drive Differently Up until this point, my mentor has suspected, with his experience in car following models, that the different styles of parametric models, developed based on vastly different heuristics, will have distinct strengths and weaknesses when compared to human driving behavior. After weeks of deep literature review, we reached consensus to test our dataset on five different car-following models of various origins, to represent a diverse population of models. For the next three weeks, I dedicated my nights and days into building an efficient GPU-based simulator so that parallel parameter search and optimization for each of these models can be completed efficiently. This was a period of intense programming, where my skill of replicating ideas from literature was intensely trained.

def simulate_step(self, t, hp): # t is timestamp, an index, hp is a dict of hyperparams, which is passed to various places

if self.pred_field == PRED_ACC:

self.a_pred[...,t] = self.calc_a(t, hp)

# Clip velocity output to non-negative values

self.v_pred[...,t+1] = torch.maximum(self.ZERO, self.TICK * self.a_pred[...,t] + self.v_pred[...,t])

# Clip acceleration values to 0 if velocity was clipped

self.a_pred[...,t] = self.a_pred[...,t] * torch.logical_not(torch.logical_and((self.v_pred[...,t]==self.ZERO), self.v_pred[...,t+1]==self.ZERO))

self.x_pred[...,t+1] = self.x_pred[...,t] + self.v_pred[...,t] * self.TICK + self.a_pred[...,t] * self.TICK**2 / 2.0

self.s_pred[...,t+1] = self.lv_x[...,t+1] - self.x_pred[...,t+1]

self.relv_pred[...,t+1] = self.lv_v[...,t+1] - self.v_pred[...,t+1]

elif self.pred_field == PRED_VEL:

self.v_pred[..., t] = self.calc_v(t, hp)

self.a_pred[..., t] = self.TICK * 2 * (self.v_pred[..., t] - self.v_pred[..., t-2]) # Average acceleration

self.x_pred[...,t] = self.x_pred[...,t-1] + self.v_pred[...,t] * self.TICK + self.a_pred[...,t] * self.TICK**2 / 2.0

self.s_pred[...,t] = self.lv_x[...,t] - self.x_pred[...,t]

self.relv_pred[...,t] = self.lv_v[...,t] - self.v_pred[...,t]

else:

raise Exception("Unknown Prediction Parameter!")PyTorch-based Parallel Car Following Simulation

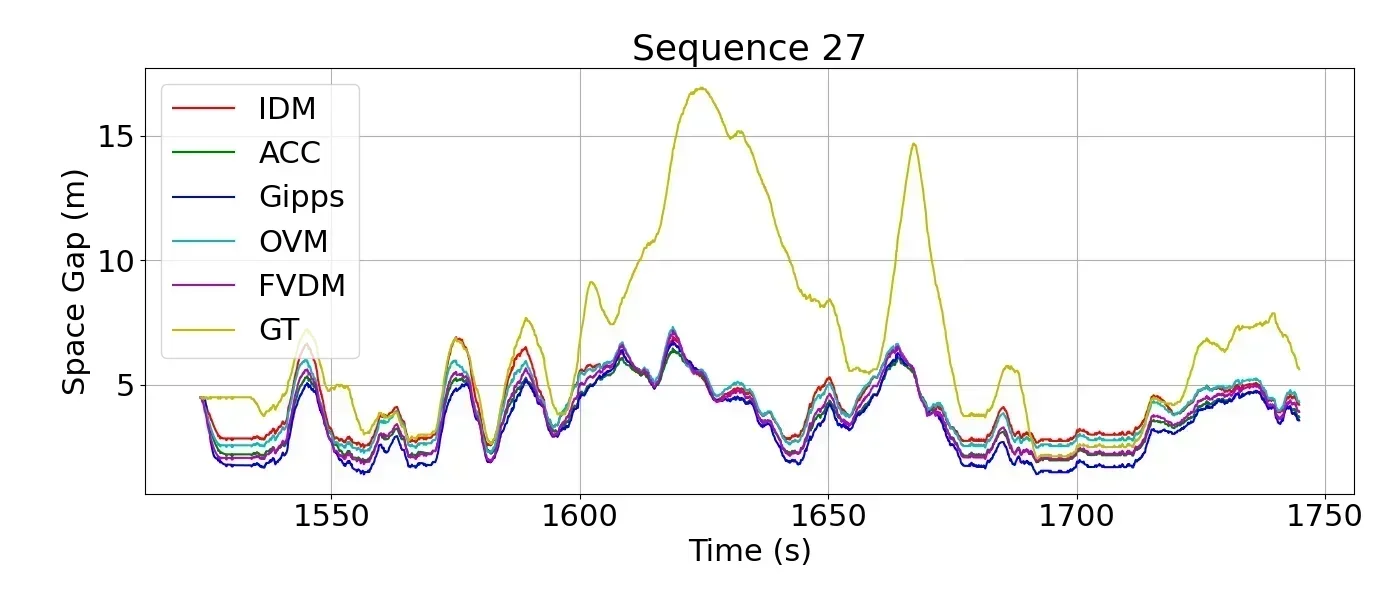

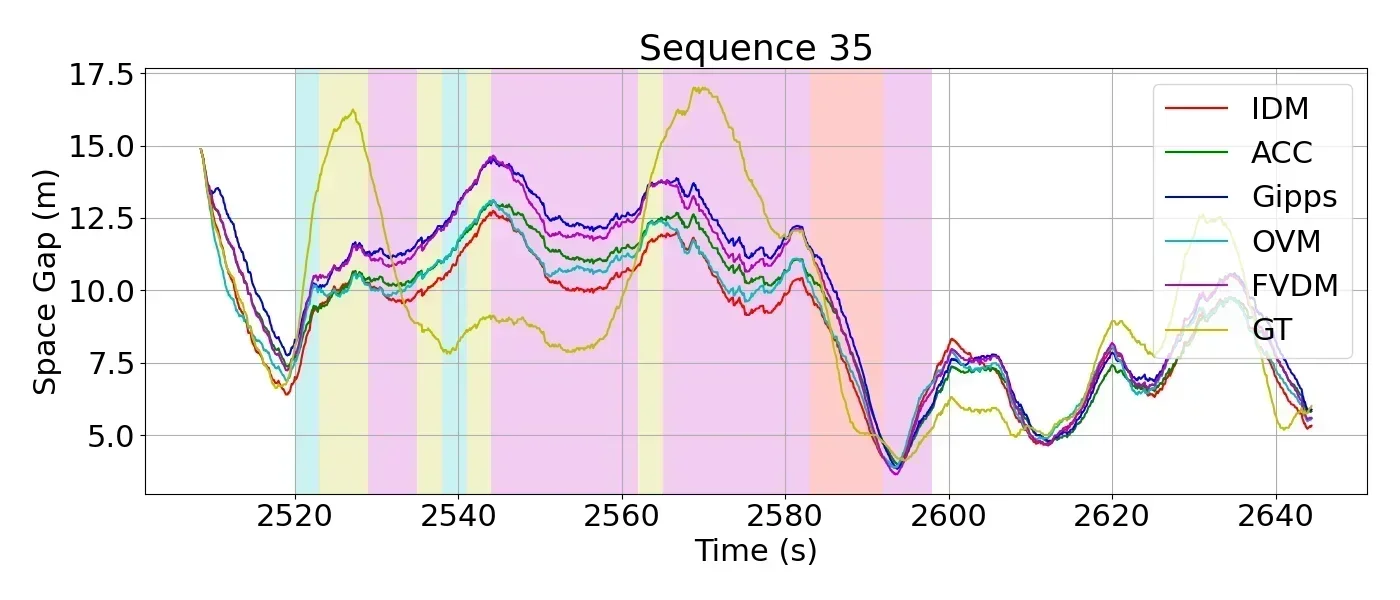

Eventually, my simulator was bug-free enough that it is producing stable and reasonable results for all available data. I was finally able to run the parameter optimizaiton for the five models and produce graphs about their optimal car-following behaviors. The metric used in this field to tune the models is not entirely agreed upon, but the debate seems to be only between MSE, RMSE, and RMSNE. I adopted RMSNE for the normalization behavior since I hypothesize that the error scale matter a lot more in a congestion scenario, where the ratio of max/min speed is large. Eventually, I produced graphs that looked something like this.

These lines look pretty close, right? In fact, they are statistically pretty close. It turns out, that when you optimize towards a unified goal, in this case, RMSNE, the optimized parameters make the model behaviors converge. So our question was answered: there isn't much of a difference between the models when they are optimized over the same objective. Not very interesting Huh. I thought the same. Yet, there is one distinct feature in these graphs that I thought was worth taking a look at.

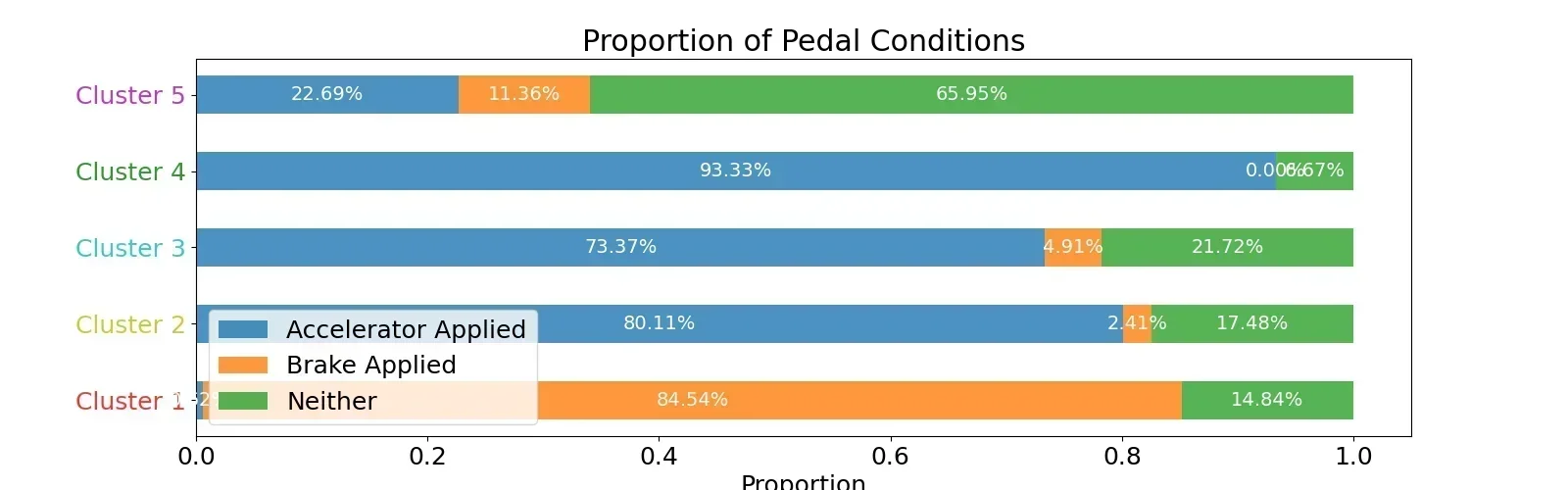

How Human Drives Differently I noticed that the driver sometimes drives almost exactly like the model would predict, but other times would produce very different behaviors. Noticeably, human drivers often have larger standard deviation in their following-distance, and often leaves large gaps to the lead vehicle for extended periods of times that is not explained by any of the models. After spending three days reviewing camera footage and associated driver input data, I was surprised to notice that drivers are often not pressing any pedals at all during a congestion. Unlike parametric car-following models which actively switches between acceleration and deceleration with no phase-change reaction times or "laziness" to stay at zero input, human drivers are less likely to be frequently applying or changing their pedal application. Often times, they employ the vehicle's coasting nature in high speeds and the engine's idle creep feature at low speeds, so that they can relax in the vehicle without having to actively engage with the control pedals.

To qualitatively show this, Dr. Kusari again raised a method widely accepted in the data science community: time series clustering. By clustering time series data using a kernel-based method (essentially doing a time-1D filter), we can qualitiatively suggest a difference among human driving patterns. Upon tuning for an appropriate duration of time using fit metrics and an appropriate number of clusters with the elbow method, we arrived at five clusters with 3-second long kernels.

What we found was rather interesting result: while four of the clusters encode some patterns of acceleration and deceleration, with different timing, the fifth cluster shows a distinct no-pedal pattern. This shows that our observation is confirmed in a qualitiative analysis. Furthermore, we notice that while other clusters often appear intermittently, cluster five, where drivers lift and coast, have much longer average consecutive appearance time. This means that drivers employ lift-and-coast for extended periods of time during their driving in congestions. While our congestion dataset was ultimately not large enough to conduct any further analysis of population and inter-driver differences with any meaningful significance, this study qualitatively reveals one key aspect of human driving behavior in a congestion setting that previous literature failed to model or explain.

Closing Remarks

This extraordinary summer research experience turned out to be much more than just an academic exploration: it is a voyage through the deepest of waters and highest of waves to finally embed a deeper understanding of myself and the research endeavor. The shift from autonomous driving to human behavioral analysis, topped with an unexpected shift in mentorship, thrusted me into the unknown. Yet, it was within the unknown realm where I find resilience. Sailing through the storms reveals invaluable lesssons that research is never a straight, comfortable path--it is a journey that only the bravest and most persistent conquerers can master.

Having heard of this many times from renouned scientists, I personally realize that the true insights rarely emerge from confirmation of our hypotheses, but from results that challenge them. The doubts and frustration for unexpected behavior often spark innovative ideas and catalyze deeper understanding of the subject matter. I learned to find significance in every outcome, analyzing each step to gain a deeper understanding, with the belief that a setback is always the night before the dawn of breakthrough.

This experience also forged my character to never say never, no matter what the situation is. In fact, my very final qualitative clustering results that demonstrated our hypotheses was completed during a 3 a.m. frustration in Marseilles, France, while I already started my vacation for the Olympics. I learned to treasure every opportunity for personal growth, no matter how the outcome will be. The critical thinking I nurtured, the resilience built, made me not just a better researcher coming out of this experience, but as someone ready to conquer the greatest of challenges and discoveries with my open mind that never quits.